Before I discuss this patent, let me mention my credentials. I’m not a lawyer nor a patent agent. However, in my long engineering career, I filed and received more than a few patents (all assigned to my employer). I spent many years on an invention review board, I mentored new inventors, and I was awarded a title of Master Inventor. So, I’m speaking with at least some knowledge of this stuff!

Okay – so let’s first talk about what one needs in order to obtain a patent. The invention has to meet three requirements. It must be useful, which really means it has to be something you can make work (which prevents patenting a perpetual motion machine). It must be novel, something not done or described before. And it must be unobvious to someone of normal skill in the art, which is many times the most difficult one to determine.

What does it mean to be novel? Well, it can still build upon other things. So, you can’t patent a telephone, but you can patent a particular improvement to a telephone as long as the improvement meets the three requirements.

The obviousness criterion is tricky. It has to be unobvious to someone of normal skill in the art. If it seems obvious to you, you have to ask yourself am I of normal or above normal skill? The patent office will often cite literature which the examiner says “teaches” the method you’re trying to patent, or something so close that the leap to your method is straightforward.

Being on the receiving end of these (they are called office actions), they sometimes show the examiner just didn’t understand what the invention is. So, it’s a bit subjective, and there’s some wiggle room. And sometimes the examiner is just out of his or her league. Looking at a patent like this one, we wonder what prior art did the examiner look for and find. Patents often cite many other prior patents in the same general area. This one cites no issued patents (there is one patent application from 2003 cited which is strange in that this application resulted in an issued patent, so why cite the application and not the issued patent?). It cites no other prior art – no papers or books.

Now let’s discuss the parts of a patent. There’s the intro stuff: names, prior art, etc. There’s an abstract giving a brief overview. There are figures (three in this case). There is a description of the preferred embodiment. Let me explain that a bit. The reason we have patents (and they are laid out in the constitution) is in many ways to further the transfer of knowledge and techniques to the public. In exchange for doing so – telling the world how you do something – you gain the ability to prevent others from using that for some period of time (20 years from filing for utility patents). This gives people an incentive to not hold onto such things as trade secrets. That’s the idea, at least. In today’s technology world, 20 years might seem excessive.

So, one of the things you must do is describe the best way to do or make your patent. It has to be described in terms that someone of normal skill in the art can understand and replicate. That’s the preferred embodiment.

Finally, there are the claims. This is the meat of the patent from a legal point of view. You claim your invention or inventions, laid out in a way someone could test against for infringement. If it’s not covered by the claims, there is no infringement. There’s again some legal wiggle room that a judge or jury might have to decide. Within the claims section, there are two kinds of claims, independent and dependent. The value of a patent is directly related to the breadth of the claims. That is, if you’re patenting a telephone, and you claim “a device into which one speaks and a second device from which the sound of that speech emanates” it’s better (more valuable) than a claim that includes all the details of converting sound to electricity, using wires, and so on, because it potentially covers a lot more ground. So, radio devices might be covered, or two cans and a string.

The problem with broad claims is it’s more difficult to get your patent. You’re trying to cover more territory and there are more possibilities someone has done something similar already. On the other hand, if you make your claims very narrow, you make it much easier to pass the patent office since no one might have described exactly the detailed method you’re using. (Although, here the obviousness might be a factor.) Anyway, you want all your claims to be valid, but if one gets thrown out, another claim which adds more details (narrows it) might still be valid. So, there are broader independent claims and narrowing dependent claims.

I know that’s a lot to absorb, but the general public doesn’t understand any of this and tend to jump to conclusions like, “Amazon patented shooting against a white background!” Well, no, not exactly. So I got a copy of the patent from Google’s patent search, and I read it.

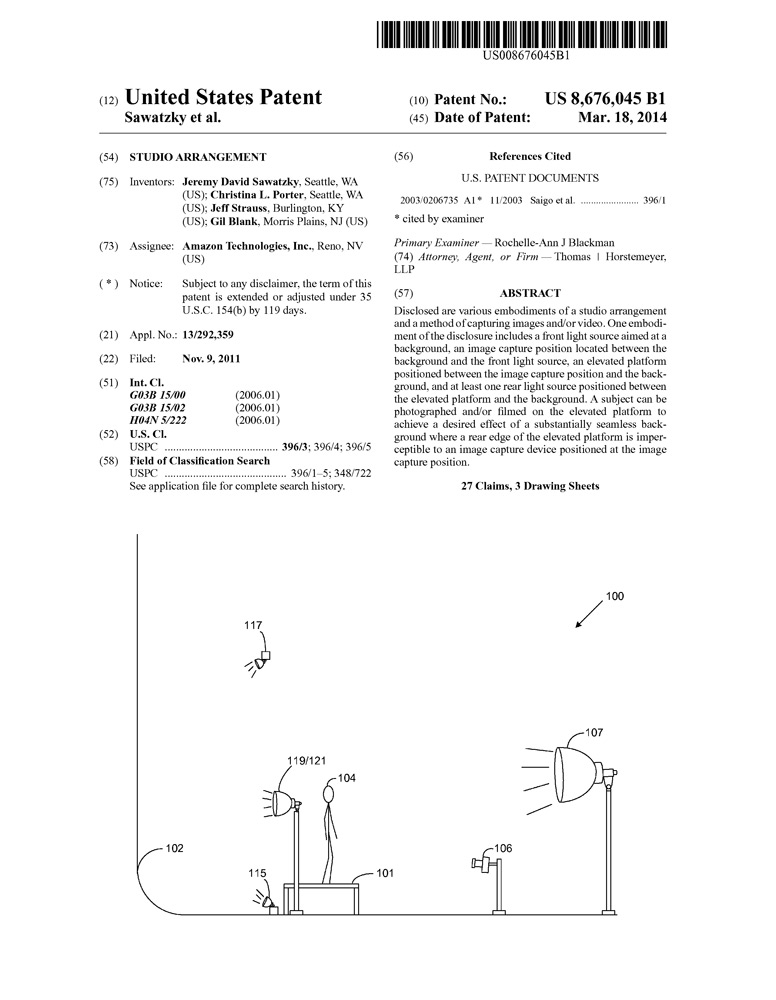

Asking the question, what problem were they trying to solve? They lay that out in the description. They want the subject to appear floating against an all-white background with a reflection below and want it to be done with no postproduction, either photographs or video. They state that prior art solutions “often involve some type of image retouching, post processing, ‘green screen’ techniques, or other special effects…”

They go on to describe a studio and lighting setup to achieve their goal. It’s pretty specific and their preferred embodiment involves around 50 kilowatts of lighting! Is there anything there that I haven’t seen before? Not much. But let’s look at the claims.

There are 27 claims. If I read them right, there are three independent claims and 24 dependent claims. Claim 1 is the first independent claims, and it’s pretty specific. It has no dependent claims. It’s the one I’ve seen mentioned in other blogs and includes things like ISO of about 320 and f-stop of about 5.6 among other things. It would seem to be pretty easy to avoid violating that claim.

Claim 2 is the next independent claim. It’s broader, but still has some specifics like the use of a cyclorama (we usually just call it a “cyc”), a front light, at least two rear lights, at least one shield (a gobo!). Most of the rest of the claims are dependent on this and add various details.

Claim 25 is the last independent claim describing a “method” rather than the studio arrangement itself. It covers putting the subject on a platform, activating the lights, and turning on the camera. It seems weird to me to have a method claim for this, but what do I know. (I know patent lawyers are sometimes paid by the number of claims, or so I’ve heard!)

So what’s the takeaway? I am surprised this patent was issued even with so many specifics and rather narrow claims. I’d have a hard time arguing this isn’t obvious to any professional photographer who routinely works in a studio with a cyc or does any regular product photography work. But, it’s been issued and Amazon now has the right to defend it using their large resources. Would it stand up to a jury? Who knows.

The other question is why did Amazon bother with this? It could be for protection – in other words, it prevents someone from filing a similar patent and then claiming Amazon is infringing. But they could probably achieve the same thing by publishing the method and making it public and, therefore, prior art preventing a patent.

It’s not the strangest patent I’ve read. But I must admit, I never expected to be seeing patents covering photographic lighting! I did think it might be an interesting one to discuss here, though. Hope it wasn’t too overwhelming!

Very informative from a unique perspective…thanks so much for sharing your take on this issue. Bobbi

Comment by Bobbi Wendt — July 21, 2014 @ 4:26 pm